Image by Chickenonline from Pixabay

Image by Chickenonline from Pixabay

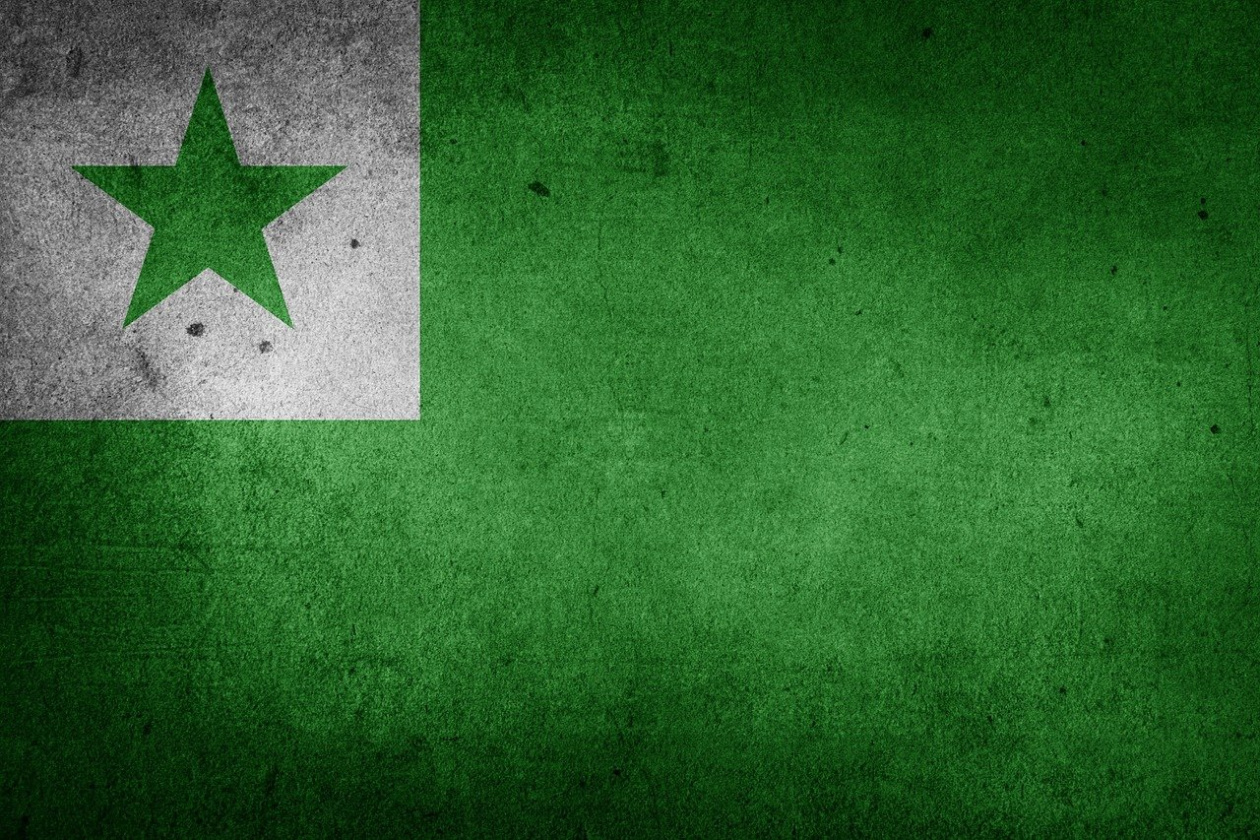

Is Esperanto beyond hope?

Ostatnia aktualizacja piątek, 25/07/2025

Esperanto was created in 1887, with the goal of becoming a universal second language, easy to learn for everyone and free from nationality.

What was your favourite way to pass the time when you were bored in math classes? For Adam Żyłka, usual activities like scribbling on paper or making little drawings on the table were not captivating enough. That’s how a 17-year-old Polish living in Madrid started learning Esperanto from Wikipedia. He started attending events organised by the Esperanto community and now, years later, he’s one of the directors of TEJO (Tutmonda Esperantista Junulara Organizo, or, in English: World Esperanto Youth Organization).

Kio estas tio? Esperanto was created in 1887, with the goal of becoming a universal second language, easy to learn for everyone and free from nationality, so that it doesn’t privilege some at the cost of others. Its association with the Jewish people and the promotion of world peace led to a crackdown on Esperantists under the Nazi and Stalinist regimes, but it has survived still, and continues to offer an alternative to hegemonic languages. Its founder, Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof, was convinced that “every nationalism offers humanity only the greatest unhappiness”.

The simplicity of the language can be explained chiefly due to its lack of exceptions and by the way words are created by prefixation and suffixation. It’s also said that, after learning Esperanto, it becomes easier to learn other languages; not only is that Adam’s personal experience, having learned his 6th and 7th languages after Esperanto, but it’s also backed by the Paderborn method, which has been studied by the University of Essex and many others.

The logic is simple: once you know a given word, you can easily make new ones by adding a prefix or a suffix; for example, you add “-ejo” for places related to the word in question. If “lerni” is the verb “to learn”, how could you say school? Lernejo. The same goes for vendejo (shop), juĝejo (court), and all other places. Since there are no exceptions to the rules, knowing a handful of them will render you an already good understanding of Esperanto. The advocates recognise that much vocabulary has its roots in Romance languages, with hints of Slavic, Germanic and Greek, but still defend that it's easier to learn for most people than English or French.

Even if it’s easy to learn, a common objection persists. “Why not stick with English?” the reader may ask, since so many people already learn it as a second language. Adam warns this is a common misconception: most people in the world (around 80%) don’t speak English, according to Statista/Ethnologue. Even those who do often lack the necessary proficiency and self-confidence to actually use the language and fully communicate with others, prompting Gloria, in the famous show Modern Family, to shout (“do you even know how smart I am in Spanish?!”). Finally, favouring native speakers of the Commonwealth is far from being equitable, rendering non-natives in a worse position.

And how is Esperanto doing in the EU? The language does not have the backing of the European Commission as it “would take a lot of time and resources” and reaffirmed its “commitment to multilingualism promotes diversity rather than uniformity” in a memo from 2013.

I reached out to Nela Riehl, Chair of the Parliament Committee on Culture and Education, who added that “since Brexit, English is a second language for most EU citizens, thus not giving particular advantage to individuals in the institutions and fulfilling the same role Esperanto could have”. She notes, however, that “It has played a crucial role in bringing people together across languages and cultures, and the Esperanto society has always been in favour of democracy and internationalism”. In Hungary, Esperanto is accepted as a living language and admissible as proof of competence in a foreign language in university admission.

Since May 2024, it’s possible to learn Esperanto on Duolingo, which has prompted the joke, Adam told me, that “it’s the only language one can really learn on the app”. You can also try platforms such as Esperanto12 and Lernu.

Still, the language doesn’t have more than two million speakers worldwide, on its most favourable estimates, which often results in the vicious cycle of lack of motivation to learn because not enough people have learnt it yet.

Since UNESCO’s General Conference’s recognition of the “great potential of Esperanto for international understanding and communication among peoples of different nationalities” in its 1985 resolution, many people have joined both the language and the movement. Adam, TEJO, and all others will keep advocating for this cause, teaching it and adding value to it. But it’s up to each of us to decide: is Esperanto beyond hope, or will we make it part of our collective life?

Young Journalists in Europe - Meet the author

Guilherme Alexandre Jorge (Lexi)

“You can call me Lexi. I'm navigating Law, Consulting, Journalism and Politics.

When not promoting a European Federation or participating in Erasmus+ projects, I may be found reading, working out, writing poetry or making dad jokes. And I'm a swiftie. I like to write about things I believe we can fix together. And together we can fix almost everything.”

Article collaborator: Efe Yalabikoglu, Friederike Kroeger

This article reflects the views of the authors only. The European Commission and Eurodesk cannot be held responsible for it.