Source: Wikimedia Commons

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Flares of Polarisation: How Spanish Wildfires Were Used to Fuel Political Divide

Zuletzt aktualisiert am Freitag, 28/11/2025

As Spain burned this summer, thousands of hectares transformed into a desolate, dark landscape, the country’s politicians were absorbed in a game of accusations and rebukes. While the people screamed for help, how did we let political polarisation stifle their cries?

Most destructive wildfires in years

August passed with devastating consequences for the Spanish state. Less than a year after being stricken by the destructive DANA floods, this past summer, Spain faced a very different kind of disaster, one that has relentlessly consumed its fields. More than ten high-scale fires were declared during the last month of the summer; one of them, affecting the provinces of Zamora and Leon, in the Northwestern part of the country, has been pronounced the worst fire Spain has faced this century.

The burnings provoked forced relocations, destroyed entire villages and even caused several deaths, including civilians, volunteers and firefighters. A resident from Cernego, an affected village, described their despair to the newspaper El Debate Galicia: “Our world crashes down. It is horrible to see this. Burnt memories, only these four walls remain standing. We, people in small villages, have been completely abandoned”.

Although the worst seems to have already passed, several fires remained active in the areas of Galicia and Extremadura as late September.

Fires are nothing new to the Spanish during the summer months. But why have they hit with such unprecedented violence and strength this year? Several factors have converged, namely the lack of effective fire prevention, the abandonment of the Spanish countryside by young people, and the ever-looming presence of the climate crisis, which is turning our summers into a suffocating hell. The lack of suitable prevention policies has been matched with regrettable management by the regional and central governments.

Indeed, beyond the flames, politicians are engaged in a parallel battle where the suffering of the people is perceived only as political ammunition.

Reproaches and accusations

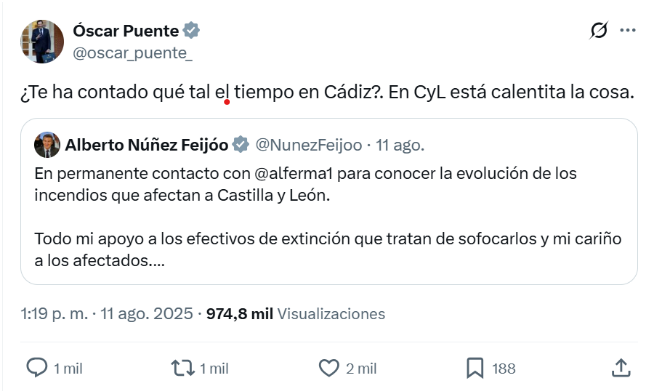

“Did he tell you about the weather in Cádiz? In Castilla y León, things are heating up.” With these words on X on the 11th of August, Oscar Puente, the socialist minister of transport, addressed the leader of the opposition, Alberto Nuñez Feijóo. In his tweet, he alluded to the holidays Alfonso Férnandez Mañueco, president of the region of Castilla y León, seemed to be enjoying in the Andalusian city of Cádiz. All while the territory under his charge was consumed by fires. Not for the first time, Puente was heavily criticised for his controversial tweets, this time trivialising the consequences of the fires.

However, accusations were not one-sided: barely two days later, in an interview with Europapress, Nuñez Feijóo condemned President Pedro Sánchez’s response to the emergency: “The central government remains on holiday”. Reproaches and complaints have been thrown from one side to the other in a political picture where the polarisation of leaders and citizens governs every interaction.

Source: Screenshot from Minister of Transport Óscar Puente’s X account, dated 11th August 2025.

“Polarisation refers to the growing tendency to move towards the political and ideological extremes on issues related to the public space,” explains Mariano Torcal, Political Science Professor at Pompeu Fabra University, as we speak this September. As distance grows between oneself and their opponents, taking the first steps towards a compromise is deemed an act of betrayal. “Politics is a synonym of negotiation,” explains Torcal. Because of polarisation, effective political action is often blocked.

In Spain, polarising inclinations are aggravated by the country’s institutional design, which divides power between the regional and central governments. Currently, the Popular Party rules in 11 of the 17 autonomous communities that form the Spanish state, whereas the Socialist Party, in power in the central government, controls only 4. In situations of emergency or natural disaster, such as these fires, the limits between the competencies of each level of government become blurred.

In these cases, “the idea of an inefficient state is instrumentalised in the public discourse”, explains Torcal. The recent management of the wildfires exemplifies this tension: “When you adopt a strategy of constant agitation where you do not recognise any merit of the enemy and the enemy is to blame for everything, inaction occurs”.

Unsettling trend in Europe

Rather than an isolated case, the rapport between political polarisation and an inefficient crisis management response in Spain needs to be contextualised within the wider scenario in Europe. According to Torcal, polarisation in Europe “follows more or less the same lines [as in Spain], although with many nuances”.

In Italy, Meloni’s decision to delegate the reconstruction in the area of Emilia-Romagna after the devastating 2023 floods to an independent party rather than the left-wing regional authorities seems to also obey this trend. That same year, wildfires in Greece sparked fierce politics of blame, this time directed towards immigrants.

Is there anything we can do to stop this impasse? Torcal remains sceptical: “There is no easy solution,” he says. According to him, this is particularly true if we consider that polarising tendencies within traditional media outlets are not likely to disappear. On the contrary, scandal and outrage are increasingly valuable means to attract the reader.

An alternative path passes through the dynamics of citizen dialogue: “It has been proven that the theory of deliberation favours a decrease in polarisation,” admits Torcal. That is, the idea that a just and functional cohabitation can only be achieved if citizens are allowed to participate freely and equally in the public discourse. According to this theory, if we were to put citizens in a room and leave them to deliberate without external influences, they would come up with good, effective solutions. Still, its effects remain short-term; the moment we leave these dialogue spaces and become exposed once again to the current framings in radios, newscasts or newspapers, we are back to square one.

Demonstration against the wildfires’ management in Segovia, taken by Arturo Francisco Barbero on the 3rd September 2025. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Today in Spain, fires are already extinguished. Entire villages face the daunting task of reconstruction, working their way through rubble, collapsed roofs and burnt walls. And still, beyond substantial material and environmental losses, Spanish society has been further wounded, in a subtler yet dangerous manner. Indeed, the flares of polarisation might prove harder to put out than wildfires.

Young Journalists in Europe - Meet the author

Ángela Garrido Rivera

“As I finish my EU Competition Law Master I see the European Youth Portal as the perfect scenario to combine my fascination for EU affairs with my biggest passion: storytelling.”

Article collaborators: Anna Kalenichenko, Luiza Elena Zob

This article reflects the views of the authors only. The European Commission and Eurodesk cannot be held responsible for it.